Thursday, April 25, 2024

“Zuri Burns” – A Sift Among the Ashes

Cover of a multi-DVD set about the Zurich occupation movement

I was afraid of Zurich. I passed through the airport years ago on a two-leg flight. The border agents contemplated deporting me for Schengen over-stay, even though I was on my way to the USA. I paid $50 for lunch. Saw the private jets parked in a line on their own runway. Spied some of the beautiful people strolling by. “This is another world,” I thought, and it’s not mine.

But I really wanted to learn about the intense squatting and occupation movement of the 1980s that gave rise to the Rote Fabrik cultural center, and the people who fought so hard against the police in the private banking capitol of Europe.

So we went. Yes, it’s expensive, but you can catch a meal in a box at the Coop supermarket and eat it on a bench by the river. And if you figure out the tram system you can swing around the city like a monkey through the trees. In short, it’s doable. Plus I bought a cool used raincoat for 15 francs.

The story of the Zurich squatting movement offers an important urban model of motivated popular development. And it’s still happening.

The movements which began with a bang in Zurich in 1980 have had two important outcomes – the Rote Fabrik cultural center, and the Kraftwerk 1 cooperative housing development. Squatting is ongoing, with new occupations popping up regularly. The artists, the punks, and the working classes all have a good chance in Zurich at what they call “social luxury”.

I only met a few people, and I wasn’t an energetic ethnographer. But the visit did clear up one strong misconception I have held.

Forget New York

Ten years ago, in Occupation Culture, I proposed the "New York model" of a squatting movement in which artists played a central role. This was against (or with) the assumption that politicals alone do effective squatting.

After my visit to Zurich I can see that the model of occupations driven by culturally-engaged people is a general one, not at all special to NYC. You can indeed create the conditions in the city in which you wish to live. You simply need a little more of what Matt Metzger once called “sand”. (And be ready to sacrifice your NYC “real world” career.)

The squat-based cultural scene in NYC is static. There have been no new actions of public building occupation since the wild ‘90s, and some of those that existed are legalized. The management of the few tiny cultural institutions that came out of it, and the valorization of their legacies are sustained by the work of a handful of aged activists.

The Zurich scene, like that in Madrid where I live, is multi-generational. New occupations are driven by young people who are working within a well-defined tradition with an intelligent set of playbooks and creative tactics.

Not So Cold, but Everything Closed

I picked a bad time to visit. The weather was nice, though. Like everywhere now, spring came early. The forsythia were blazing yellow along the banks of the Limmat, and we didn’t need our heavy jackets. But it turned out the Shedhalle, the contemporary art section of the Rote Fabrik cultural center, was closed for reconstruction. The two major left infoshops, the Fermento and the Kasama were also closed.

I just missed crossing paths with expat squatter artist and musician Peter Missing (#petermissing), who offered to take me to the “post office squat”.

So I parked for a few days in the Sozialarchiv, a small palace of study to see what I could make of the movement I had assumed was definitively in the past.

Image from a period journal from the K-set archive

The movement, as it turns out, is very well historicized. A tremendous five-CDROM set of videos explains the Zurich movement from the ‘60s through the ‘80s over eight hours of video and narration. This is built off the archives of efficient and energetic street media collectives back in the day. Hausbesetzer-Epos: allein machen sie dich ein (2010) is an effective and affecting overview.

One of the librarians kindly gifted me an extra copy she had of the basic history of the movement, Wo-Wo-Wonige (2006). And I picked up a copy of a recent history of the Rote Fabrik Bewegung tut gut – Rote Fabrik (2021) at the cooperative bookstore in the Volkshaus. So I have plenty to chew on with my limited German.

It will take me a time to absorb it.

The Red Factory

I did wander the Rote Fabrik during a rainy weekday when it was all but deserted. The Shedhalle art exhbition and event space – (to call it a “museum” is wrong; it’s more like a cultural generator) – was under renovation. It was full of scaffolding and workers. The cafe was locked up. A few men were working setting lights in the theater, a well-appointed space painted black which adjoined a small bar room.

I wandered the corridors. The stairwell is decorated with posters of past events. All the studios were closed. In a classroom space with windows overlooking the yard I saw the backpacks of the young people who looked out curiously at me as I passed the printing studio. They were receiving a lecture there.

The Fabrik is on the edge of the lake. There’s a dock; in fact there’s a ship-building workshop and a boating club. Surely a pleasant place in the summertime.

A Bit’o bolo-bolo

As for the huge cooperative housing project recently constructed, I did not visit, nor even learn about it until later. Comrades from NYC are well acquainted with the Swiss urbanist Hans Widmer who strived to imagine a “anti-capitalist social utopia”. His “bolo” concepts are reflected in the Kraftwerk 1 development.

I didn’t get to see Kraftwerk 1. Widmer’s publisher (and also mine) was to visit just after me, and he and his partner stayed there. (Blogger turning green.) Miguel Martinez, my onetime comrade in our late squatting research group SqEK, also visited last year as part of the INURA conference. They gave him the 10-cent tour, and he produced a reflection on his visit, a text called “Social Luxury”.

In Kraftwerk 1, individuals have small rooms, sleeping spaces, and access to large common areas like kitchen, living rooms, library, and laundry. This is the format of the Ganas commune in NYC where I lived for some months. Ganas had TV rooms in its different houses, as well as music rehearsal and media production rooms. And a swimming pool.

The housing cooperative includes a food depot linked to a garden coop, a rural link Widmer considered vital for his urban bolos.

Miguel maintains that Kraftwerk 1 living “provides happiness” through increased social life. This is a project, and requires work; living in common is demanding. I recall the strong centripetal force of the Ganas commune. No one really wanted you to leave, to spend your day outside the compound.

He writes of “communal social security” during moments of crisis, and the general support in all the mundane tasks of living, especially childcare. This is a true thing which I have observed. Commune babies are famously self-reliant people, full of confidence and unafraid of the most precarious of life strategies – being an artist.

Despite the great advantages of this mode of living, it is not for everyone. It can be hard work. Ganas spent a lot of time on conflict resolution, and the magazine Communities devotes a lot of space to the question.

Overall, conceptions and realities of “social luxury” both are over-shadowed by a world in which we are endlessly treated to visions of private luxury. The sense of perpetual dissatisfaction that motivates so many aspects of life under capitalism can make even a utopia seem like a drab and confining place.

Not to me.

Writing about this now, and thinking back on my brief time in Ganas makes me sad and envious. Sad that so few of us can have these expanded possibilities in our lives, and envious that, despite the present luxurious fulfilment of my materials needs, I am among the excluded.

Well, I’ve dipped my toe into the Zurich experience here, and there’s a lot more to come. Those Swiss are clever, and have indeed figured a lot of things out that many in Europe and USA could learn from.

LINKS

Midnight Notes, “Fire and Ice: Space Wars in Zurich”

The original brilliant description of the movement, including their innovative tactics

https://theanarchistlibrary.org/library/midnight-notes-fire-and-ice-space-wars-in-zurich

Schweizerisches Sozialarchiv

https://www.sozialarchiv.ch/

Doris Senn, Mischa Brutschin, Hausbesetzer-Epos : allein machen sie dich ein (2010)

https://scholar.archive.org/work/n4fp4q6ghnexhn3ynw7qvcuvpq

T. Stahel, Wo-Wo-Wonige! Stadt- und wohnpolitische Bewegungen in Zürich nach 1968 (2006)

Internet Archive Scholar

https://scholar.archive.org › access › https: › eprint

Interessengruppe Rote Fabrik (Hg.), Bewegung tut gut – Rote Fabrik (2021)

Martínez, Miguel A. (2023) On social luxury. Some reflections resulting from the INURA meeting, Zurich, 2023.

https://www.miguelangelmartinez.net/?Social-luxury

p.m. (Hans Widmer), bolo’bolo (2011, 1984, Autonomedia)

INURA – 2023 – Zurich -- International Network for Urban Research and Action

https://inura23.wordpress.com/

Kraftwerk1

https://www.kraftwerk1.ch/

An ETH Zürich design studio project from spring, 2023, explicates Hans Widmer's ideas and Kraftwerk 1 --

https://topalovic.arch.ethz.ch/Courses/Student-Projects/FS23-Bolobolo-Utopia-Within-Reach

Communities magazine, formerly published by Foundation for Intentional Community, which maintains a global directory of collective living projects at https://www.ic.org/

Onetime squatter artist Ingo Giezendanner, aka Grrrr, holds one of his meticulously drawn books. They'll be at the Allied Productions booth at this year's NY Art Book Fair, as Ingo has visited and worked at Petit Versailles

Friday, December 15, 2023

Madrid Anarchist Book Fair: The Sap Is Rising

Your blogger tables at another book fair, this one at the popular school La Prospe in Madrid. All my stock is old, but I’m planning new research and reporting on the new ‘commonsing’ (open, assembly-run, not publicly administrated) citizen action spaces which are sprouting anew in the Spanish capitol. This post discusses some of these new initiatives, and gets into the library with some recallings of Chicago hobo eggheads and Surrealists.

After my fun experiences at the Pichifest zine festival (blogged previously), I was primed for the Madrid anarchist book fair at La Prospe. That self-organized place is a libertarian free school which is celebrating their 50th anniversary this year.

I felt a basic elation to be again in the middle of this kind of cultural action in autonomous space. My Spanish is poor. I understood about 20-30% of what was going on. But everyone was polite, even friendly to this old man with his small spread of radical books on squatting.

I’d received no response to my request to join. “We had so many proposals,” the woman hosting said when I arrived as the doors opened. “But I can give you this little bookstand.” She dragged it into the front room and I plopped my stuff down. I set up the “House Magic” zines on the chalk shelf of a blackboard, the pages resting in the white dust of past writing.

Those zines are old stuff: “House Magic: BFC” (Bureau of Foreign Correspondence), my project from 2009 to 2016. Along with this blog, those zines fed into Occupation Culture: Art and the City from Below (Minor Compositions, 2015), and Making Room: Cultural Production in Occupied Spaces (JoAAP & Other forms, 2015), the anthology that SqEK research group members contributed to. (Both are free PDFs online.)

House Magic: Bureau of Foreign Correspondence working research office, Produced by Alan W. Moore and the ABC No Rio Visual Arts collective for the University of Trash, Sculpture Center NYC, 2009. Photo by Jason Mandella at michaelcataldi.com.

All of that work is ancient in internet time; Google has demounted the original “House Magic” site with PDFs of the zines. (They are scattered around elsewhere.) That site was built when the ABC No Rio visual arts collective put up the exhibition in 2009 that began my researches.

But after a long interregnum I am back at it. The time is ripe. A revitalized commonsing movement is rising again in Madrid. When the right took over city government in 2019 with the help of the neo-fascist Vox party, they immediately began a campaign of eviction against citizen-run spaces across Madrid, both squatted and permitted.

They cancelled contracts for several permitted centers which had been many years in operation, thereby greatly annoying neighborhood organizations that were not radical left. They evicted a roster of okupas, which are always vulnerable, climaxing with the centrally located Ingobernable. (The building has remained empty despite government promises, which is quite typical.) With the Covid virus fear and lockdown in full swing, it was hard to muster crowds to defend these spaces, although people did come out in hundreds on the streets against some of these moves.

So Vox got their red meat: The centers of Venezuelan- and George Soros-inspired communist indoctrination were closed. And the neo-fascists march on with a culture war agenda targeting any LGBTQ representations. Vox pols are mounting a concerted attack in the cultural arena across Spain, a complement to De Santis' crusade in Florida, and radical Christians throughout the small towns of provincial USA.

But true to the axiom that repression breeds resistance, the movements have been reconstituting themselves with a strong effective organization. Their sap is rising now, with more motivations, and consequently a broader base of support, than in the past. With rampant gentrification and a debilitated public health system – (both the responsibility of the city and provincial governments) – political imperatives are stronger than ever.

A recent article in ElDiario.es, "La nueva estrategia”, explains the complex organization of the resistance, and the actions that are unfolding. The neighborhood movements are bolstered by organizations based in rented or owned premises -- Ecologistas en Acción, Fundación de los Comunes, and Traficantes de Sueños and others -- which have expanded their facilities and produced programs in support of the commonsing projects. What is new this time is the clearer emphasis on the provision of space for culture and free sociality.

The Cultural Turn

Groups which have run what we might call “social centers” are renting and buying spaces. How they constitute themselves, their public faces, are also changing. The article notes several projects, including Ateneo La Maliciosa and La Villana de Vallekas. La Maliciosa is a large recently-opened space close to the Lavapiés neighborhood, a collaboration between the above-named groups and the bookstore/publisher Traficantes de Sueños.

Like La Prospe and its innumerable anarchist ancestors in Spain, La Maliciosa is an ateneo, a space for meeting and learning. La Villana is in the peripheral barrio of Vallecas. The space they are working towards was a tavern. It will continue as such, and include a bookstore. Both these places were crowd-funded, with a built-in intention to “generate money that can be put in the service of political ends”.

What clearly links all these projects, almost irrespective of their divergent political positions, is a desire to organize and produce their own cultural and social projects and events without having to engage with and navigate scarce public resources and official administrative apparati.

It is a good moment to pick up the strings of the project I dropped eight years ago – the grail of my SqEK days, a “popular book of squatting”. That is the volume that will life the scales from people’s eyes by demonstrating historically how important the movement of occupied collectively organized social centers has been.

“La nueva estrategia” is just that, the new strategy for a kind of organizing that has been rolling continuously for decades. The March, 2015 document, “Manifiesto por los espacios urbanos de Madrid”, was circulated at a more hopeful moment. I translated and posted it here as “The places where the future is invented”. That post is hyperlinked to many of the projects of that moment, some of which survive.

Quite a lot has changed in the intervening years since that manifesto appeared, and even more since I proposed the “popular book” project to our group. There is change in the overall situation in which the squatting movement finds itself, changes in its public face, and for me, changes in how I think my researches should be reported.

Ontology of Self-Publication

The general questions around how to go forward with my researches and reportings is somewhat clearer after these two fairs. Writing academic articles does nothing for me; I stopped long ago. I think there’s no point in aiming for finished books, since there’s so little audience and so little response. Still, as with avant-garde art it’s not how many it’s who. Maybe I flatter myself that the “House Magic” zine series 2009-16 helped to animate occupations in the USA during those years of strikes and OWS.

Limited audience means limited editions. I’m going to continue to both blog online and “zinefy” in print. I’ll work myself more closely into the production process of the publications as well as researching and writing. I’ll learn bookbinding.

Research Campaign

I went into the book fair with a boost from the lovely folks at the Archivo 15M who put my call for collaborators on their blog. They also sent along a dossier of documents about the post-15M occupation project Hotel Madrid. I’m not holding my breath that such folks will, like elves, magically appear. The immediate question is how to gather the resources I need to make these zines.

At the Feria, I met an elder from an archive I didn’t know existed. It’s the Fundación Salvador Seguí, which is something of a cousin to the FAL-CNT archive and bookstore. With sites here and in Barcelona and Valencia, the mission of the FSS is “to collect, organize, preserve and disseminate documentation related to the libertarian movement”, which is exactly what I’m trying to do.

I’m confident now I can find the research resources I need to make the project possible.

Finally, These Are Book People

Third day of the anarchist book fair. I'm in the big room, awaiting the presentation of the Grupo Surrealista, “Towards a new romanticism: revolutionary and anti-development while capitalism destroys the world”. It was delivered by the author of a recent pamphlet, and I found it entirely incomprehensible. The discussion began with “the question that André Breton posed to the unknowable just at the moment of his death: ‘What are the true dimensions of Lautréamont?’ ” Hmmm....

As it was with that talk, I was slow to catch the matter of the many titles on display. But after browsing for three days I found several titles to grapple with.

A Deeper History

I was emboothed at the fair next to Pepitas de calabaza, a publisher with a large list and a full table. Almost out of the corner of my eye I spied their Spanish edition of Boxcar Bertha, a novel by Ben Reitman (1937), set in “hobo jungles, bughouses, whorehouses, Chicago's Main Stem, IWW meeting halls, skid rows and open freight cars”. Word is “Bertha” was likely an amalgam of historical personages; Reitman was a lover of Emma Goldman. It was made into an AIP flic directed by Martin Scorsese in the ‘70s. Reitman’s 1937 book is pretty little known, but it’s an important part of hoboing subculture, that is today, the thinking train-hopping crust punk.

As it happened, when I passed through Chicago picked up a copy of From Bughouse Square To The Beat Generation by Slim Brundage, with a foreword by Franklin Rosemont. Brundage came on the Chicago scene later than Reitman, but had similar ways and ambitions. The Rosemonts revived Charles H. Kerr, the IWW’s old publishing house. The Rosemonts are also beloved of the Grupo Surrealista folks. All that long-gone Chicago scene is getting hot again as it was the subject of a chapter in Abigail Susik's recent book Surrealist Sabotage and the War on Work (2021).

I was happy to share a copy of that book. I have bad Spanish, and I’m certainly an armchair anarchist, but in the end these are book people, and we all share a love of the ones that excite us.

Chicago, the Nation’s Railyard

The Chicago nexus, the early 20th century U.S. anarchist movement which saw the proliferation of Ferrer schools, named for the murdered Spanish educator – all this harks back to an era of international solidarity and a relatively free movement of peoples across borders which brought these movements into conjunction. The hobo intellectuals whom the Chicago Surrealists loved were of a piece with the Spanish anarchist movement which at the turn of the century launched hundreds of ateneos libertarios, libertarian free schools to educate the laboring classes. Workers in the 19th century in Spain were at the mercy of the Catholic church for what minimal public education was provided. School was – and still is – a drilling in wage labor discipline.

Punk zine table at anarchist book fair. "Every weekend at the Rastro I have a table", said this participant

To get away, to escape, to reach any wider plain of understanding of one’s own situation together with others, and the burden of the broader human condition needs schooling. Even in many cases un-schooling. This the ateneos libertarios provided.

That this situation is essentially unchanged – that government-provided education remains a contested political terrain – brings us back to La Prospe, the host site for this and last year’s anarchist book fair.

NEXT: La Prospe, the 50-year-old libertarian school in Madrid.

LINKS

A note to fans: Tired of the incessant spam. I've reset comments to "only members", which I think means you have to follow this blog to comment.

XXI Encuentro del Libro Anarquista de Madrid 1, 2 y 3 de Diciembre 2023

https://encuentrodellibroanarquista.org/

“La nueva estrategia de los movimientos vecinales de Madrid: rearmarse en locales autogestionados” (The new strategy of Madrid's neighborhood movements: rearming in self-managed premises) A new surge in social center activism in Madrid is taking a cultural focus.

https://www.eldiario.es/madrid/somos/nueva-estrategia-movimientos-vecinales-madrid-rearmarse-locales-autogestionados_1_10709115.html

“Manifiesto por los espacios urbanos de Madrid” circulated in 2015, translated and posted here as “The places where the future is invented”

http://occuprop.blogspot.com/2015/03/

Ecologistas en Acción

https://www.ecologistasenaccion.es

Ateneo Maliciosa

https://ateneomaliciosa.net

CIUDAD OKUPA

Derecho a la ciudad, centros sociales, precarias y territorios QUEER.

https://traficantes.net/nociones-comunes/ciudad-okupa

My call for Madrid collaborators on the Archivo 15M blog

"Se buscan colaboradorxs para fanzine okupa"

https://archivosol15m.wordpress.com/2023/11/29/se-buscan-colaboradorxs-para-fanzine-okupa/

October 2011 “OccuProp” blog post on my visit to the Hotel Madrid "Welcome to the Hotel Ocupa"

http://occuprop.blogspot.com/2011/10/welcome-to-hotel-ocupa.html

Rocío Lanchares Bardají, Hotel Madrid, historia triste (2021) a kind of fictional history of 15M and the Hotel occupation. Presentation of the book online; "Hotel Madrid, historia triste"

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1topsI-1Sq4

Fundación Salvador Seguí

Centro de estudios libertarios fundado en 1986 para recopilar, ordenar, conservar y divulgar la documentación referente al movimiento libertario.

https://www.fundacionssegui.org/

Fundación Anselmo Lorenzo - CNT

https://fal.cnt.es/

Website of the author of the Grupo Surrealista book presented at the fair

vicentegutierrezescudero

https://vicentegutierrezescudero.wordpress.com/tag/grupo-surrealista-de-madrid/

Ben Reitman, Boxcar Bertha

https://www.pepitas.net › libro › boxcar-bertha

En este texto, original de 1937, Ben Reitman narra la vida de Bertha Thompson, una mujer que fue prostituta, ladrona, reformadora, trabajadora social, ...

in English: Sister of The Road: The Autobiography of Boxcar Bertha, as told to Dr. Ben Reitman (AK Press, 2002)

Slim Brundage, From Bughouse Square To The Beat Generation with a foreword by Franklin Rosemont https://charleshkerr.com › books

The writings collected here by the College's founder and janitor, Slim Brundage (1903–1990), chronicle the colorful history of what may well be the oldest ...

Tuesday, November 7, 2023

Art + Squat = Pichifest

It’s been a busy time above ground these Days of the Dead. I spent those holidays preparing publications and displays for the Pichifest zine fair here in Madrid. I was glad to be in town for this one, and Friday was the day…

First a run to a morning meeting of the assembly of the Archivo Sol (Centro de Documentacion 15M) at the 3 Peces 3 center in Lavapies. Arriving late, I pitched a proposal for a series of zines to the small group of archivists assembled there. The 3P3 storefront is small, and since my last visit it’s been redesigned. It seems much larger. It’s cleaned and clear, with shelved books from floor to ceiling on every wall.

I made zines out of my blog posts, the ones especially germane to the theme of a zine fest in an occupied space. “Art + Squat = X”, of course, a 2010 text recently translated into Portuguese and published in Brazil; and a couple of talks I gave at the Reina Sofia about New York City art stuff – NYC in the ‘80s, and films of David Wojnarowicz. Those texts were well translated, not by machine.

Future Plans

My proposal to 3P3 is to make a series of zines about famous occupied social centers in Madrid. There have been many, most long since evicted, but these projects are little known today. Recovery work on radical history, is always important since it gets silted over so quickly in the media environment. But this work seems more urgent now since the great break in action which the pandemic and its lockdowns created.

The Black Lives Matter movement arose in the USA from urgency despite the prohibitions on gatherings. Today many of the mass protests against the Israeli bombing of Gaza are proceeding despite government proscription. But the quotidian occupations in Madrid were evicted during lockdown because the activists couldn’t muster the crowds to defend them. There is a need now after some years of the Forgetting to reintroduce the most successful and inspiring projects of the occupation movements to younger people who are its potential activists.

“It isn’t left-wing, Marxist or anarchist,” I declared. “It’s anti-capitalist adventure!”

It’s what folks can do to break the stranglehold institutions and governance have over both culture and politics. There are clear precedents and procedures for squats and occupations of all kinds, “rulebooks” as it were, which have been published. Some have gone through many editions.

Interchangeability

One realization came from a suggestion made by one of the assembly at 3P3 – she’d been a bibliotecaria at the long-evicted CSO Casablanca where Archivo Sol had its first site. She suggested I visit with the group of filmmakers, documentalistas at 3P3, who have made work on the okupas and social centers in Madrid. They have scripts for those moving image projects, and archives, texts and images used in the development of their films which can be the building blocks for publications.

Blog = zine = film.

“Terror/Error" Amongst the Creepers

This edition of the Pichifest was held at La Enredadera (the Ivy) in the barrio of Tetuán. It's a squatted space, a cavernous delapidated building with three floors. The 1st floor (2nd US) had factory-type skylights, although we couldn't be under them because they leak in the rain. Sorry, no photos – the assembly of La Enredadera prohibited them.

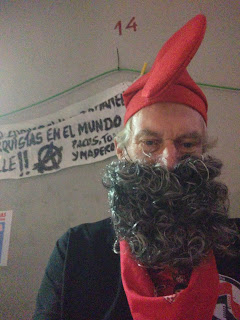

The theme of the fair was "Terror/Error", and the organizers asked presenters to come in costume. I chose gnome (el gnomo), which is a common off-the-shelf costume ensemble here.

The gnome has radical connotations. It was a kind of insignia for the Dutch movement of Kabouters. I read the recent Autonomedia book by Coen Tasman Clearly Kabouter: Chronicle of a Radical Dutch Movement, 1969-1974, when Jordan Zinovich was getting it into shape. “Kabouter” is Dutch for gnome. I also attended a presentation by Major Waldemar Fydrych when he launched his book on the Orange Alternative activism in Poland in the ‘80s. The Orange folk also embraced the gnome identity as they deployed their "socialist sur-realism" in absurd street-painting and large-scale performances comprising tens of thousands of people dressed as dwarves. Fydrych handed out orange gnome hats at the NYC event.

“Lose the Beard,” She Said

This is pretty obscure. Of course I had to explain it to anyone who even glanced at my table. Actually, the organizers’ suggestion to come in costume was brilliant. It cut the weird vibe in all art fairs of this kind, between the browsing spectator and the anxious artist who is desperate to explain themself to all and sundry. Being in costume takes the edge off that interaction. Folks can just smile at your character without having to engage the material you display.

Prep – preparation of the display – was a lot of work. I cut a stand out of a cardboard box, painted it, put in wooden struts, and draped it with fabric to hold my zines. Most of those are pretty old stuff, principally the “House Magic” series from 2009 to 2016. (The PDFs used to be online, but Google demounted the site, and the mirror site was hacked and never repaired, so… get ‘em in paper or forget ‘em. [That’s not totally true; see links below.])

My 2015 book was based on the "House Magic" zines. Cover by Seth Tobocman.

I have some new stuff: “Martin Wong en sus proprios palabras”, with texts in Spanish by Martin Wong, Barry Blinderman, Miguel Piñero, Yasmin Ramirez, et al. Martin’s show is touring Europe – it opened in Madrid, and is now in Amsterdam. And, as mentioned above, several hastily “zineified” blog posts.

“Celebrate Peoples History”

As it turned out the hit of my booth was the venerable “Peoples History” poster series curated by Josh MacPhee of the Interference Archive. I had copies of the first volume of his Celebrate People’s History in book form, and many color printouts of the posters in A3/ledger size. These were left over from the 2019 exhibition of the series at ABM Confecciones in the Vallecas barrio of Madrid. That was a great show, but a fracaso in terms of attendance, with even the jokers from Carabanchel who produced JACA (Las Jornadas de Arte y Creatividad Anarquista de Carabanchel), of which the ABM show was a part, not bothering to attend. (Kvetch, kvetch, but really, you don’t build a scene unless you support it with your body.)

The Pichifest offered this extraordinary material a second life in Madrid.

Text Message Log

Friday, 6:15 PM

Gnomo: Pretty fantastic space. No fotos allowed, however. [Squatters often prohibit photos of their sites.] I can foto my own stuff I assume.

She: Very good. I like it

Gnomo: There is light enough to read by, but it's not a good "selling environment".

She: Put more zines visible, and the books in the rack. It is difficult to see the house magic stuff.

Gnomo: People are stopping. It's obviously about squatting. I don't think people are that interested in squatting. If they are, nothing will stop them from engaging. Plus most of it's in English. Mostly the stuff here is "arty", about cartooning and the like.

First sale! Martin Wong. And a conversation....

Now it's really crowded – 7:22 pm

A Slovenian guy passed by. He worked in the infoshop in Metelkova! Very political...

[This fellow was wearing a Lenin cap, and didn’t speak Spanish. He didn’t think much of my stuff.]

Mainly I am getting ideas about how to do this again, and better.

[The first “Celebrate Peoples History” sells. It is the “Co-Madres” poster from El Salvador. The young woman who bought it said, “I heard about this from my aunt. She’s going to love this. She is a graphic designer.”]

Another Slovenian passed by...

The zinester in costume, with a house-made poster on the wall in background

She: Remove the beard please!!

Gnomo: One hour and 15 minutes to go.... this is actually work! – 8:45 pm

The guy next to me arrived late. It seems he has dozens of friends.

[That was a young cartoonist – Miguel, @ekim.comics – The fellow on the other side of him was dressed as a ghost.]

I'm packing up... and along come a couple of archivists! They wanted to buy things I can't sell. One said, "Now I have long teeth for these" [“se me ponen los dientes largos”].

What I could not sell; only one copy

Gnomo: La comida de cena fue rico. Tacos veganas.

Saturday 12 noon to 20:

[I amped up the “Peoples History” poster display.]

Gnomo: My neighbor today is dressed like a rock

She: And your display?

I lucked out to be next to the Erededera supply shelves so I could hang up the posters. You should come! It's very relaxed and fun.

They're pouring in now -- 2PM

I'm fading. I'll try to give it another hour to catch the after-lunch crowd – 5:15pm

This hat actually is pretty warm. Silly but functional. Those gnomes knew a thing or two

The explanation of the "rock man"

She: Que tal va todo?

Muy bien. Al final uno de los organizadores pasan y compran. Hablamos y voy a hacer un entrevista con la colectiva

She: 👏👏👏

Gnomo: My neighbor gave up. I squatted his space

"Big rush at the end" he said, and it's true.

Now the posters are selling fast.. -- 7:30pm

Crazy last minute when everything sells... I'm out of here now. -- 8:45pm

She: You must be exhausted

GnomoNot so bad when there's a lot to do. No customers and the time drags painfully.

NEXT: Hopefully an interview with the Pichifest crew.

LINKS

Pichifest linktree

https://linktr.ee/pichifest

Centro Social Tres Peces Tres

https://3peces3.wordpress.com/

“Art + Squat = X” text

Art + Squat = X (ENG) // Arte + ocupações = X (PORT)

by Alan W. Moore, City University of New York (PhD): NYC, NY, US

Henrique Piccinato Xavier, traductor

Universidade de São Paulo (USP) São Paulo SP, Brasil

Estado da Arte, Uberlândia, Brazil. 3 n. 1p. 345 - 383 jan./jun. 2022

Portal de Periódicos UFU

https://seer.ufu.br › article › download

"Arte en Nueva York en los ochenta: Espacio, Permiso, Aspiración" [2 parts; also in English]

http://artgangs.blogspot.com/2014/07/arte-en-nueva-york-en-los-ochenta_25.html

"Deathtripping: Filming the East Village"(1980–1989); July 2019

(This talk was not blogged)

https://www.museoreinasofia.es/en/activities/deathtripping-filming-east-village

Clearly Kabouter: Chronicle of a Radical Dutch Movement, 1969-1974, by Coen Tasman

https://autonomedia.org/product/clearly-kabouter-chronicle-of-a-radical-dutch-movement-1969-1974-by-coen-tasman/

Lives of the Orange Men A Biographical History of the Polish Orange Alternative Movement by Major Waldemar Fydrych (Author); Gavin Grindon (Editor); Yes Men (Foreword)

https://www.akpress.org/lives-of-the-orange-men.html

Google has gobbled up its older sites, like House Magic - Google Sites

Oct 24, 2013 · Bureau of Foreign Correspondence "House Magic: Bureau of Foreign Correspondence" is an ongoing informational project about the global movement of direct …

maybe try the Wayback Machine? Or… Archive.org, has some --

https://archive.org/details/house_magic_1

“Peoples History” poster series

https://justseeds.org/format/peoples-history-poster/

Celebrate People’s History: The Poster Book of Resistance and Revolution, edited by Josh MacPhee. 2020. 264 pages. This is volume 2.

A visual representation of people's history through political posters.

https://www.zinnedproject.org/materials/celebrate-peoples-history

Art Gangs blogspot, “Interference Archive: de Brooklyn a Madrid”

Una exposicion del autonomo Interference Archive con carteles de la serie "Celebrate Peoples History”, con catálogos y revistas, y otra propaganda gráfica producido por miembros de JUSTSEEDS, una red norteamericano de artistas radicales, trabajando para y dentro de movimientos sociales.

Fue parte de JACA 2019 extendida

http://artgangs.blogspot.com/2019/06/intereference-archive-de-brooklyn-madrid.html

Laura L. Ruiz, “La otra cara del barrio de Carabanchel: JACA, la creatividad anarquista,” 06 junio 2019

https://elasombrario.publico.es/carabanchel-jaca-creatividad-anarquista/

El Comité de Madres de los Desaparecidos y Asesinatos de El Salvador (Co-Madres)

https://justseeds.org/product/co-madres/

Poster from Half Letter Press

First a run to a morning meeting of the assembly of the Archivo Sol (Centro de Documentacion 15M) at the 3 Peces 3 center in Lavapies. Arriving late, I pitched a proposal for a series of zines to the small group of archivists assembled there. The 3P3 storefront is small, and since my last visit it’s been redesigned. It seems much larger. It’s cleaned and clear, with shelved books from floor to ceiling on every wall.

I made zines out of my blog posts, the ones especially germane to the theme of a zine fest in an occupied space. “Art + Squat = X”, of course, a 2010 text recently translated into Portuguese and published in Brazil; and a couple of talks I gave at the Reina Sofia about New York City art stuff – NYC in the ‘80s, and films of David Wojnarowicz. Those texts were well translated, not by machine.

Future Plans

My proposal to 3P3 is to make a series of zines about famous occupied social centers in Madrid. There have been many, most long since evicted, but these projects are little known today. Recovery work on radical history, is always important since it gets silted over so quickly in the media environment. But this work seems more urgent now since the great break in action which the pandemic and its lockdowns created.

The Black Lives Matter movement arose in the USA from urgency despite the prohibitions on gatherings. Today many of the mass protests against the Israeli bombing of Gaza are proceeding despite government proscription. But the quotidian occupations in Madrid were evicted during lockdown because the activists couldn’t muster the crowds to defend them. There is a need now after some years of the Forgetting to reintroduce the most successful and inspiring projects of the occupation movements to younger people who are its potential activists.

“It isn’t left-wing, Marxist or anarchist,” I declared. “It’s anti-capitalist adventure!”

It’s what folks can do to break the stranglehold institutions and governance have over both culture and politics. There are clear precedents and procedures for squats and occupations of all kinds, “rulebooks” as it were, which have been published. Some have gone through many editions.

Interchangeability

One realization came from a suggestion made by one of the assembly at 3P3 – she’d been a bibliotecaria at the long-evicted CSO Casablanca where Archivo Sol had its first site. She suggested I visit with the group of filmmakers, documentalistas at 3P3, who have made work on the okupas and social centers in Madrid. They have scripts for those moving image projects, and archives, texts and images used in the development of their films which can be the building blocks for publications.

Blog = zine = film.

“Terror/Error" Amongst the Creepers

This edition of the Pichifest was held at La Enredadera (the Ivy) in the barrio of Tetuán. It's a squatted space, a cavernous delapidated building with three floors. The 1st floor (2nd US) had factory-type skylights, although we couldn't be under them because they leak in the rain. Sorry, no photos – the assembly of La Enredadera prohibited them.

The theme of the fair was "Terror/Error", and the organizers asked presenters to come in costume. I chose gnome (el gnomo), which is a common off-the-shelf costume ensemble here.

The gnome has radical connotations. It was a kind of insignia for the Dutch movement of Kabouters. I read the recent Autonomedia book by Coen Tasman Clearly Kabouter: Chronicle of a Radical Dutch Movement, 1969-1974, when Jordan Zinovich was getting it into shape. “Kabouter” is Dutch for gnome. I also attended a presentation by Major Waldemar Fydrych when he launched his book on the Orange Alternative activism in Poland in the ‘80s. The Orange folk also embraced the gnome identity as they deployed their "socialist sur-realism" in absurd street-painting and large-scale performances comprising tens of thousands of people dressed as dwarves. Fydrych handed out orange gnome hats at the NYC event.

“Lose the Beard,” She Said

This is pretty obscure. Of course I had to explain it to anyone who even glanced at my table. Actually, the organizers’ suggestion to come in costume was brilliant. It cut the weird vibe in all art fairs of this kind, between the browsing spectator and the anxious artist who is desperate to explain themself to all and sundry. Being in costume takes the edge off that interaction. Folks can just smile at your character without having to engage the material you display.

Prep – preparation of the display – was a lot of work. I cut a stand out of a cardboard box, painted it, put in wooden struts, and draped it with fabric to hold my zines. Most of those are pretty old stuff, principally the “House Magic” series from 2009 to 2016. (The PDFs used to be online, but Google demounted the site, and the mirror site was hacked and never repaired, so… get ‘em in paper or forget ‘em. [That’s not totally true; see links below.])

My 2015 book was based on the "House Magic" zines. Cover by Seth Tobocman.

I have some new stuff: “Martin Wong en sus proprios palabras”, with texts in Spanish by Martin Wong, Barry Blinderman, Miguel Piñero, Yasmin Ramirez, et al. Martin’s show is touring Europe – it opened in Madrid, and is now in Amsterdam. And, as mentioned above, several hastily “zineified” blog posts.

“Celebrate Peoples History”

As it turned out the hit of my booth was the venerable “Peoples History” poster series curated by Josh MacPhee of the Interference Archive. I had copies of the first volume of his Celebrate People’s History in book form, and many color printouts of the posters in A3/ledger size. These were left over from the 2019 exhibition of the series at ABM Confecciones in the Vallecas barrio of Madrid. That was a great show, but a fracaso in terms of attendance, with even the jokers from Carabanchel who produced JACA (Las Jornadas de Arte y Creatividad Anarquista de Carabanchel), of which the ABM show was a part, not bothering to attend. (Kvetch, kvetch, but really, you don’t build a scene unless you support it with your body.)

The Pichifest offered this extraordinary material a second life in Madrid.

Text Message Log

Friday, 6:15 PM

Gnomo: Pretty fantastic space. No fotos allowed, however. [Squatters often prohibit photos of their sites.] I can foto my own stuff I assume.

She: Very good. I like it

Gnomo: There is light enough to read by, but it's not a good "selling environment".

She: Put more zines visible, and the books in the rack. It is difficult to see the house magic stuff.

Gnomo: People are stopping. It's obviously about squatting. I don't think people are that interested in squatting. If they are, nothing will stop them from engaging. Plus most of it's in English. Mostly the stuff here is "arty", about cartooning and the like.

First sale! Martin Wong. And a conversation....

Now it's really crowded – 7:22 pm

A Slovenian guy passed by. He worked in the infoshop in Metelkova! Very political...

[This fellow was wearing a Lenin cap, and didn’t speak Spanish. He didn’t think much of my stuff.]

Mainly I am getting ideas about how to do this again, and better.

[The first “Celebrate Peoples History” sells. It is the “Co-Madres” poster from El Salvador. The young woman who bought it said, “I heard about this from my aunt. She’s going to love this. She is a graphic designer.”]

Another Slovenian passed by...

The zinester in costume, with a house-made poster on the wall in background

She: Remove the beard please!!

Gnomo: One hour and 15 minutes to go.... this is actually work! – 8:45 pm

The guy next to me arrived late. It seems he has dozens of friends.

[That was a young cartoonist – Miguel, @ekim.comics – The fellow on the other side of him was dressed as a ghost.]

I'm packing up... and along come a couple of archivists! They wanted to buy things I can't sell. One said, "Now I have long teeth for these" [“se me ponen los dientes largos”].

What I could not sell; only one copy

Gnomo: La comida de cena fue rico. Tacos veganas.

Saturday 12 noon to 20:

[I amped up the “Peoples History” poster display.]

Gnomo: My neighbor today is dressed like a rock

She: And your display?

I lucked out to be next to the Erededera supply shelves so I could hang up the posters. You should come! It's very relaxed and fun.

They're pouring in now -- 2PM

I'm fading. I'll try to give it another hour to catch the after-lunch crowd – 5:15pm

This hat actually is pretty warm. Silly but functional. Those gnomes knew a thing or two

The explanation of the "rock man"

She: Que tal va todo?

Muy bien. Al final uno de los organizadores pasan y compran. Hablamos y voy a hacer un entrevista con la colectiva

She: 👏👏👏

Gnomo: My neighbor gave up. I squatted his space

"Big rush at the end" he said, and it's true.

Now the posters are selling fast.. -- 7:30pm

Crazy last minute when everything sells... I'm out of here now. -- 8:45pm

She: You must be exhausted

GnomoNot so bad when there's a lot to do. No customers and the time drags painfully.

NEXT: Hopefully an interview with the Pichifest crew.

LINKS

Pichifest linktree

https://linktr.ee/pichifest

Centro Social Tres Peces Tres

https://3peces3.wordpress.com/

“Art + Squat = X” text

Art + Squat = X (ENG) // Arte + ocupações = X (PORT)

by Alan W. Moore, City University of New York (PhD): NYC, NY, US

Henrique Piccinato Xavier, traductor

Universidade de São Paulo (USP) São Paulo SP, Brasil

Estado da Arte, Uberlândia, Brazil. 3 n. 1p. 345 - 383 jan./jun. 2022

Portal de Periódicos UFU

https://seer.ufu.br › article › download

"Arte en Nueva York en los ochenta: Espacio, Permiso, Aspiración" [2 parts; also in English]

http://artgangs.blogspot.com/2014/07/arte-en-nueva-york-en-los-ochenta_25.html

"Deathtripping: Filming the East Village"(1980–1989); July 2019

(This talk was not blogged)

https://www.museoreinasofia.es/en/activities/deathtripping-filming-east-village

Clearly Kabouter: Chronicle of a Radical Dutch Movement, 1969-1974, by Coen Tasman

https://autonomedia.org/product/clearly-kabouter-chronicle-of-a-radical-dutch-movement-1969-1974-by-coen-tasman/

Lives of the Orange Men A Biographical History of the Polish Orange Alternative Movement by Major Waldemar Fydrych (Author); Gavin Grindon (Editor); Yes Men (Foreword)

https://www.akpress.org/lives-of-the-orange-men.html

Google has gobbled up its older sites, like House Magic - Google Sites

Oct 24, 2013 · Bureau of Foreign Correspondence "House Magic: Bureau of Foreign Correspondence" is an ongoing informational project about the global movement of direct …

maybe try the Wayback Machine? Or… Archive.org, has some --

https://archive.org/details/house_magic_1

“Peoples History” poster series

https://justseeds.org/format/peoples-history-poster/

Celebrate People’s History: The Poster Book of Resistance and Revolution, edited by Josh MacPhee. 2020. 264 pages. This is volume 2.

A visual representation of people's history through political posters.

https://www.zinnedproject.org/materials/celebrate-peoples-history

Art Gangs blogspot, “Interference Archive: de Brooklyn a Madrid”

Una exposicion del autonomo Interference Archive con carteles de la serie "Celebrate Peoples History”, con catálogos y revistas, y otra propaganda gráfica producido por miembros de JUSTSEEDS, una red norteamericano de artistas radicales, trabajando para y dentro de movimientos sociales.

Fue parte de JACA 2019 extendida

http://artgangs.blogspot.com/2019/06/intereference-archive-de-brooklyn-madrid.html

Laura L. Ruiz, “La otra cara del barrio de Carabanchel: JACA, la creatividad anarquista,” 06 junio 2019

https://elasombrario.publico.es/carabanchel-jaca-creatividad-anarquista/

El Comité de Madres de los Desaparecidos y Asesinatos de El Salvador (Co-Madres)

https://justseeds.org/product/co-madres/

Poster from Half Letter Press

Tuesday, July 4, 2023

In Venice with Marco Baravalle of S.a.L.E. Docks -- Part Two

Assembly of the "Biennalocene" in Venice

While in Venice this spring I spoke with Marco Baravalle, a principal in the autonomous art space S.a.L.E. Docks. He told me about the place and its politics, part of the wave of “Occupy”-era commonsing from over a decade ago. In this second part of the interview, Marco discusses the network of social centers of the northeast of which S.a.L.E. is a part; the new governance of Italy by a fascist-descended political party; the resistance to giant cruise ships entering Venice; the relationship of S.a.L.E. Docks to the Biennale; the "Dark Matter" exhibition of 2018, and much more.

Marco and his colleagues are on to other things now. For this biennale summer season, S.a.L.E. Docks has launched a program of discussions and assemblies about precarious labor in the cultural sector.

The "Assemblea di Biennalocene" [#biennalocene] strikes against “the idea of not being able to say no to iniquitous working conditions [because of] the feeling that there is always someone ready to take our place, even in worse conditions…. So let's break isolation, get organized, let's make sure that the other person isn't the one who replaces me, but the one who supports me, stands by me.”

Marco Baravalle and his Milan colleague Emanuele Braga were just in Lisbon to talk about the manifesto of a Universal Basic Income. That’s what they are doing now…

But in this second part of our April interview we talked about the project of the S.a.L.E. Docks itself.

AWM: You said, “Sale survived for 15 years because we are part of a city and regional network of other occupied spaces”. How does this kind of solidarity protection work?

MB: It’s more than a solidarity. We are an actual organization, where each social center has its own autonomy, but the general political line that we follow is discussed in an assembly of each social center which gather more or less once a week. And it has been such for many years now. Maybe we have a few differences, but this is our great strength, this network of social centers. It’s closer than a network, it’s not that loose. It’s called Centri Sociali Del Nord Est, Northeastern social centers. And it puts together, it includes six or seven social centers from six or seven cities in Veneto, and beyond Veneto, one in Trentino.

AWM: There have been many attempts to organize social centers in Spain. But the organization fades away, and when the right wing comes to power in a city, they start to pick them off. This is what happened in Madrid, they started to close them, and there wasn’t a strong coordinated resistance; only isolated demonstrations by those affected.

MB: I don’t know what will happen here. I don’t want to lie. We are very united, but the situation in Italy sucks. The political atmosphere is very bad. We have signals that in some of the cities the municipality wants to evict social centers. We will try to be together, and this has been working for the last 20 years. We didn’t have any evictions. No matter what political color was in charge, either nationally or locally, we were able to defend our spaces. That’s why Sale is still there. The mayor of Venice was a right wing mayor, very conservative, an entrepreneur and ultra-neoliberal. So far he didn’t really try to evict us, not because the Sale Docks collective is so strong per se, but because he knows that if he wants to evict Sale Docks he will have to deal with Morion, with Rivolta, he will have to deal with different situations. He will be met with resistance. And that is something we are still able to put on the ground. I think that this municipality is not ready to pay this political price. I don’t know if it’s going to be like this forever. Things are getting worse on a general level. So we expect, for example, new attacks from the institutions. We expect new attacks from street fascists. Because it’s unfortunate – it’s their time. We are sort of resilient, but the wind is not blowing our way. But so far this unity helps us. We have social centers in Venice, in Marghera, which is part of the Venetian mainland, in Padova, in Vicenza, in Schio, in Trento, and each social center has its own satellite projects. So maybe like a boxing gym, for example, or a beautiful space in Vicenza, Caracol Olol Jackson in honor of a comrade who died too young. They have a peoples’ hospital with doctors volunteering, from dentists to psychologists. They have an osteria, a popular restaurant. They have run a great food bank during the pandemic for mainly migrant families who could not provide food for their kids.

AWM: That is returning to the Leoncavallo social service provision idea.

MB: But all over Italy, one of the few positive things about the pandemic was that it fueled a great wave of mutual aid, which is older than Leoncavallo. It has its roots in 19th century workers mutualism structures. Here in Venice we organized during the pandemic groups which went to buy food for elderly people who could not go out, or financial aid for families who were struggling because they lost their jobs. Or even online help for students – especially women, who were burdened with all this reproductive labor during the pandemic. And this happened all over Italy. This was a great thing to see happen, and it was mainly carried out by social centers, self-organized groups. This was another thing in which social centers were involved. As well, Morion has been involved with the Comitato No Navi (No Big Ships Committee) since it was founded in 2012. [This is the campaign to keep giant cruise ships out of Venice.]

AWM: I got a flag to send to Brooklyn, the Interference Archive. [It was delivered in May].

MB: Fantastic. Since then it was really the place, the engine of the committee. The committee is much larger than simply radical activists. It includes young and old people, people from different classes, from different political orientations, but the energy, the propulsion of the committee really came from Morion and the group of Morion.

AWM: I wanted to roll back to the questions around art. Morion seems to be very much embedded in its role as a center of nightlife. It’s a beautiful space. It’s perfect for that. Wandering around we passed a tiny little hole in the wall which says, “This is the only nightclub in Venice”, somewhere around Dorsoduro. That’s clearly not true. Morion is clearly the nightclub of Venice. With a very strong group of young women, they were all getting ready for Friday night when we passed by. And also Sale Docks, it’s a contemporary art space. It’s beautifully fixtured. There’s such a clear role for these places. Among the different social centers in Madrid there are some that are historically self-isolating, preserving their subculture. There are others that seem better integrated into their neighborhoods. Historically some social centers in Madrid have had close relations with institutions. The Laboratorio okupas 1, 2 and 3 inspired the program of the institutional Casa Encendida, as an exhibition of their history now acknowledges. On the other hand, La Ingobernable was evicted as soon as the right wing too over city government. And the institution with which it had the closest relation, as well as geographical proximity was dissolved. The Medialab Prado building, purpose-built for them, is now a redundant museum of historic art, one of many such useless, moribund institutions in Madrid. That question about the relation between institutions and occupied social centers, resistant spaces which understand themselves as resistant to neoliberal market models and top-down institutional governance – that relation with normative cultural institutions is important. In the SqEK research group we talked about institutionalization like it was a dirty word. But sometimes occupations become normative art institutions, like the Shedhalle in Zurich, Metelkova in Llubjana.

I was reading Pierpaolo Mudu, an academic who was involved in the Roman social center movement, and he writes that one thing social centers do in Italy is stand in opposition to mega-events. Like the No TAV movement against the high-speed railway, for example, with which the Catanian centers are deeply involved. And this gives the centers and their activism an international presence, and resonance. So Sale Docks in relation to the Venice Biennale is in a really key analogous position. You did the “Dark Matter Games”.

MB: With Gregory Sholette.

AWM: This project spoke to the issue of labor – the “dark matter” of the artworld. I discussed that essay with Greg when he started it. I was studying artists collectives for my PhD. I looked to the studies of Pierre Bourdieu, Lawrence Alloway, Howard Becker, and before that Alois Riegl, at the field of cultural production to analyze more broadly rather than only to look at the super stars. They of course are market investments. You don’t want them to fail. It’s like a bank failure if suddenly Warhol or Basquiat or Jasper Johns plummets in value. These artists must hold their value. And the “dark matter”, which Greg Sholette analyzes is like the general economy, that is everybody working. In the Accademia [museum of classic Venetian art] here in Venice they have stuck videos about all the people who maintain the artwork, restore it and so forth. All these people are the “dark matter” of classic art in museums.

MB: First of all Sale is not against the Biennale. The Biennale is an important part of what Venice is. It helps Venice from falling into provincialism, into localism. The problem with the Biennale is that it has been neoliberalizing itself a lot, at least from the ‘90s onwards. The Biennale is not something that is helping Venice develop its own art scene. It contributes to a model of Venice as simply a touristic city, as a place where people come and consume culture, in this case contemporary art, and then they go away. This leaves nothing in terms of cultural aliveness in Venice, and then the scheme repeats itself year after year after year. It also helps real estate rent to parasite on art. In the Biennale period there are hundreds of exhibitions all around the city. These exhibitions are maybe very radical in content, but they all pay the rent to big real estate owners of the city. Big and small. Art in Venice is a real synonym of rent; it’s all a synonym of renting. Many in Venice present themselves as art operators, but if you look closer what they do is basically renting out spaces.

AWM: One of the top hits on the internet for the Banksy mural in Venice is from a real estate company that says, ‘Hey! It’s our palace that he painted on that is for sale!’

MB: Exactly. The Biennale is a machine which favors real estate rent a lot in Venice. The other problem is the amount of precarious labor involved in the Biennale where you meet all the shades of unpaid, black, gray [market] labor.

AWM: This is not a source of local jobs?

MB: It’s a very important source of local jobs for some. The economy of the Biennale creates firms that work in transportation, in art handling. But at the same time it is also a machine of precarious labor. It is a seasonal event in which young workers get stuck for a few years, and then they are forced to move away. It’s a city where it’s very difficult to make a stable income, to pay for rent, and so on. These are the points of view from which we criticize the Biennale at Sale Docks. We criticize it when it is a multiplier of precarious labor, and when it is an occasion for real estate frenzy. We do demonstrations, and so forth. The other problem, which is more general, is what does it mean, art in Venice? Venice works as a very prestigious place for rich people or rich private foundations to place their spaces, but there are only very rare cases in which they build a constructive relationship with the city. Art is somehow synonimized with big private capital. So Francois Pinault, big French billionaire, tycoon of luxury industry who came here around 2007-08, and first bought Palazzo Grassi, which was previously owned by Anelli family, founders and owners of Fiat factory. With this post-Fordist substitution Pinault bought Palazzo Grassi, and then invested a few millions of euros in the restoration of Punta della Dogana. The city assigned the space for 99 years. So Pinault, Thyssen Bornemiza –

AWM: Thyssen is here?

MB: Of course. The Ocean Space, which is probably the best space in their relationship with the workers, and with the territory, the city. The workers there are satisfiied with the treatment they get. But again, this Ocean Space, which is dedicated to the relationship between art and water, art and the oceans, art and climate change is directly financed by Francesca Thyssen, by the Thyssen Bornemisza foundation. Or Anish Kapoor, who buys a palazzo in Venice to install a permanent foundation. Or, even worse, the VAC foundation. The VAC foundation is now closed because of the war [in Ukraine], but the VAC foundation has a huge building at Zattere, and it’s owned by Leonid Mikhelson, who is a Russian gas oligarch, CEO of Novatech, and very close to Putin. So Venice is this type of place where all these fuckers, these rich global billionaires come and open their own exhibition spaces. Sometimes of course because they are collectors themselves, and they want to boost the value of the things they buy. Sometimes in the case of Mikhelson they want to do some art-washing, because basically he’s a fossil fascist. So Venice is this type of place. And basically Sale Docks is an attempt at –

AWM: [Shows Peggy Guggenheim’s autobiography] I bought this, I couldn’t resist. She’s kind of the original come to Venice and make a big contemporary art thing.

MB: Exactly, but those who followed were much worse. Or at least, many of them. So Sale Docks wants to be an alternative to this equation art equals money which is very clearly present in Venice. We are a self-managed space. We have our own assembly. We don’t have rigid hierarchies. We have flexible programs. We invite people to join the assembly if they want. For us art is a tool to inquire [into] reality, it’s a tool to criticially intervene within, or to participate in the struggles for the right to the city, etc. So exactly the opposite of the idea which is conveyed by these billionaires.

AWM: I was also curious about the Institute of Radical Imagination, and that network of larger solidarity which is sustained by the Reina Sofia museum. I’ve been puzzling on the question of “new institutionality” since I began working here in Europe in 2009, when I talked to Jesus Carillo. He was vague at that point, and as the years went by it became much more specific. And there ended up to be the conference in Malaga to support the Casa Invisible.

MB: “Picasso and the Ciudad Monstro”.

AWM: And I saw also Charles Esche whose institution was very important in early social practice participating in events at Sale Docks.

MB: The Institute of Radical Imagination was an idea that I think comes from the Reina Sofia museum. I was involved since the beginning more than five years ago. The idea was to create a hybrid network between these official institutions, museums like Reina Sofia, and other museums belonging to the network of the Internationale, and social centers around Europe, and dissident scholars or artists, mainly in the Euro-Mediterranean zone, although including Chto Delat in Russia, which is a collective of Russian dissidents now exiled in Berlin since the beginning of the war. And I’d say that is now beginning to work. It is an important tool to break the barriers that separate serious art, high art and activism. Through this strange even asymmetrical alliances with big institutions such as Reina Sofia, we are able to penetrate the institutional field of art and play our little struggle for hegemony there. And we get recognition from institutions. This is another valuable protection for a space such as Sale Docks, to be put on the map of international art spaces. It is also like a very interesting group of people. It creates the ground for common collaborations which otherwise would be difficult to make happen. It is a good ground for collective discussion and collective projects such as Art for UBI [Art for Universal Basic Income], or art for radical ecologies. So these are all results of the IRI. And without this permanent or continuative ground for collaboration these projects would have never seen the light.

LINKS

Part one of the interview with Marco Baravalle is here: http://occuprop.blogspot.com/2023/04/in-venice-with-marco-baravalle-of-sale.html

"Art for UBI" is part of the German pavilion of the architecture biennale in Venice this year, part of the series "Peforming Architecture"

https://instituteofradicalimagination.org/category/school-of-mutation/art-for-ubi/

S.a.L.E. Docks

https://www.saledocks.org/about

In 2015 Marco described the S.a.L.E. Docks project succinctly to the Creative Time Summit audience.

https://creativetime.org/summit/2015/09/01/marco-baravalle/

2018 "Dark Matter Games" catalogue PDF

http://www.darkmatterarchives.net/wp-content/uploads/2012/06/g_sholette_dark_matter-ALL.withnotes..pdf

Thursday, April 27, 2023

In Venice with Marco Baravalle of S.a.L.E. Docks -- Part One

Conversations at Dark Matter Games, 2017. Those I know are Charles Esche (short sleeves), Marco Baravalle (center), Gregory Sholette (speaking, holding his book "Dark Matter", and Noah Fischer (top right). Photo posted by Macao, FB macaomilano

While I was resident in Venice recently, I had the chance to speak with Marco Baravalle, a principal in the autonomous art space S.a.L.E. Docks. As its Facebook and website tell, "S.a.L.E. Docks is an independent space for arts and politics initiated in 2007 by a group of activists who decided to occupy an abandoned salt-storage docks in the heart of Venice." As well as a principal in that space, Baravalle is an academic and curator. He researches creative labor and the position of art within neoliberal economics. He is a composed, even austere figure, and although I’ve met him a few times – in Madrid, in New York where he was a research fellow at my home institution, and this time in Venice – he remains something of a puzzle. There’s a lot to unravel with S. Baravalle, not least his extensive writings and work with the Institute of Radical Imagination. And we didn’t get to most of it. But in the first instance, I present here in two parts a transcript of our interview in March where Marco speaks directly to issues around occupation and art. And explains in a nutshell the occupation movement of which he was a part, and its solidarity with the traditions of Italian partisans.

Alan W. Moore: You gave an interview to an Italian partisan organization recently, and said you began working in the Morion social center in Venice. Were you involved in the original occupation?

Marco Baravalle: I wasn’t involved, because the original occupation is from 1990. Morion has been around for decades now. This was the moment in Italy when this adventure of centro sociale began, in 1990. We are talking a decade [or so] after 1977 when the Italian social movements, especially the movement of 1977 was defeated. [Wright, 2002] It was defeated with this operation led by a judge Calogero. He was linked to the Communist Party. But the CP didn’t have a great relationship with the social movements and with Autonomia in particular. So on the 7th of April 1979 the judge Calogero ordered the arrest of hundreds of militants of the Autonomia movement all over Italy with the accusation that basically the Autonomia was behind the kidnapping of Aldo Moro. And his thesis was that [radical philosopher] Toni Negri was among the leaders of that organization that kidnapped Aldo Moro, a thing that was proved absolutely wrong and totally absurd.

Image of a demonstration from a portfolio at my-blackout.com

But basically after 7th of April 1979, that syMBolic date for the radical leftist movements of the ‘70s in Italy, it opened up this decade of desert for Italian social movements: the ‘80s. The ‘80s were a period in which the Italian economy was booming. Silvio Berlusconi opened his first private TV channels. It was a moment of market euphoria. And even culturally speaking it was a moment in which post-modernism came to occupy the cultural, philosophical and artistic scene of Italy. Somehow it was a decade that wanted to forget the so-called anni di pioMBo [the years of lead], the years, the decade of the ‘70s which was characterized by armed positions, by terrorism and so forth.

AWM: La lucha continua. [Points to poster for relief of Alfredo Cospito, in prison under harshly punitive conditions, an international anarchist cause.] This guy was not a sweetheart.

MB: No, definitely not. But at the end of the ‘80s, early ‘90s, those who were still somehow inspired by radical left social movements – some were anarchists, most were autonomists – mostly young people who wanted to restart the social movements, or restart where Autonomia got interrupted at the end of the ‘70s – began to occupy spaces. This practice of squatting spaces was already present in the movement of the ‘70s, but it became really the core stuff, the engine that made it possible for social movements to restart in Italy, and to have a sort of presence among the youth of Italy in the early ‘90s. The idea was basically the necessity to find free spaces for sociality that were free from market logic, with low prices, independent music, with the possibility to gather around values that were not the usual market values that were affirming themselves so radically in the ‘80s.

AWM: Leoncavallo was from the middle-’70s.

MB: Yes, this was already present as a practice. It started in the ‘’70s. It was interrupted in the ‘80s. And then there was a wave of occupations and social centers in the ‘90s. And Morion is exactly part of that wave. I arrived in Venice in 1989, but I only got really involved with the collective of Morion in 2005. I went to Morion before, but more as someone who went there for concerts and other initiatives that Morion was doing.

I blogged my visit to Morion earlier.

AWM: There are different generations involved in the social center movement. Leoncavallo starts from a kind of desert of social services. They want very basic things. And Morion is now a fully functional cabaret, a cultural space, with a bar, a beautiful stage, lights and everything. It seems that it comes from a cultural need, not so much from –

MB: I would say that it’s all connected. The ‘80s were a decade that saw the spread of heroin. So many people, so many activists died because of heroin. Social centers wanted to provide a safe space, a space against the sociality led by the market, and also against heroin. Heroin was seen as put into circulation by the system itself in order to destroy the will to rebel of the youth. And it worked. So in these first social centers, the slogans were for free socialization and against heroin. This was also something that characterized Morion. Morion was also a center for the struggle for housing rights. In Venice the prices of houses are crazy, rents are skyrocketing, and so on. But even then, when Venice was much more populated than now, Venice was undergoing this neoliberalization of housing rights in which you had less and less public housing and more and more houses on the market. Morion was in the struggle for housing rights. Again with this idea is to aggregate around other values that were not market values. Of course anti-fascism was and still is very important. It was and still is a staple of what Morion is. Even militant anti-fascism.

AWM: Compared to Spain, which had a fascist government for 40 years, the anti-fascism here comes out of the partisan movement.

MB: It does.

AWM: And that was armed struggle against first Mussolini, and then the Nazi occupation. The partisan movement in Spain was starving guys in the hills, and expatriate exiles. Then with the return to democracy there was a grand bargain that, although the fascists expropriated all the Republicans’ stuff, and murdered all these people and filled mass graves all over the country, we’re not going to talk about that. It’s coming back now as a return of the repressed. It’s not the kind of continuous thing that I assume is more the case in Italy.

MB: Well, the Red Brigades [Italian armed struggle group of the 1970s] saw themselves as a direct continuation of partisan struggle. They saw themselves as those who had to avenge the resistance that was, according to them, betrayed because fascism wasn’t extirpated as it should have been after 1945.

The partisans of the war era are dead by now. And the ANPI [Associazione Nazionale Partigiani d'Italia, which published the 2018 interview I cited] is a social association of Italian partisans. For many reasons it is a very noble association, and we as social centers like to collaborate with them. They do very important work on memory of the partisan struggle. But their political positions are very mild. They are linked to center left parties in Italy, and dismiss any type of militancy. Even if the situation is different from Spain, Italy is not a nation that has dealt with fascism the way it should have. Otherwise we wouldn’t have a prime minister who is a direct continuation of fascism. She comes from the MSI [Nuovo Movimento Sociale Italiano], which is part – now she founded FdI [Fratelli d'Italia] which is a new party, a new face, but the historical and political roots are within the fascist party. That’s how complicated the situation is in Italy.

AWM: That’s the federal government.

MB: But even the region of Veneto has always been very conservative. Very Catholic, and also somehow very fascist. Also with a strong, nurtured group of right wing terrorists that were based in Veneto or in Venice. People who put boMBs in the ‘70s, and people who got involved in state killings. Those terroristic acts happened in order to create disorder and to boost the repression against social movements which were very strong in the ‘60s and the ‘70s.

AWM: The fascists now are not so active in that way in Spain. When they stick their head up and start things they get legally sanctioned and resisted on the street. Many Spanish social centers are dedicated centers of anti-fascist activism.

MB: We had to fight on the street in Venice. In 2013, maybe ‘16, I don’t remeMBer, but I will check, when Forzo Nuova, one of these fortunately small, but violent radical neo-fascist parties came here. They had a whole campaign in Venice for a couple of years, to root themselves in Venice. They wanted to open their own space. They organized a years-long campaign to somehow conquer Venice from their point of view. And we had to go very radical. We had clashes with the police that were protecting the fascists in Piazza de Roma and in front of the train station.

AWM: In the U.S. there was a rise of fascists under Trump. They didn’t call themselves that. MB: Yeah, alt-right, or whatever.

AWM: And the fight against them was led by anti-fascists, anti-fa, which for some reason the news media ended up calling “an-TEE-fah”, so as not to say the “f” word, I guess. This was mostly mobilized in the anarchist milieu. A nuMBer of radical media outlets report on these fights, but the mainstream media did not choose to understand these as battles between fascists and anti-fascists in the way that would be very clear in Europe. They didn’t sympathize, or even report on anti-fascist struggles in the US, even after classical anti-semitic fascist violence in a synagogue massacre.

MB: From what I saw they criminalized the anti-fa movement. AWM: The U.S. is in denial that they had a big fascist movement during the ‘30s. Even in New York City in the ‘70s you could see Mussolini t-shirts in Little Italy.

MB: Even now. I saw them in the Bronx.

AWM: In Fordham Road.

MB: A market where you had mozzarella, and ham and Mussolini pictures all over. The Italian-American community is pretty conservative, I guess.

AWM: I lived in Staten Island.

MB: So you know.

LINKS

S.a.L.E. Docks

https://www.saledocks.org/about

In this 2015 video Marco described the S.a.L.E. Docks project succinctly to the Creative Time Summit audience.

https://creativetime.org/summit/2015/09/01/marco-baravalle/

Salvatore Marchese, “Su fascismo e antifascismo: intervista a Marco Baravalle del Laboratorioccupato Morion”, n.d. ca. 2018. Auto-xlt’d to ENG.

https://www.anpive.org/wordpress/2018/08/03/su-fascismo-e-antifascismo-intervista-a-marco-baravalle-del-laboratorioccupato-morion/

Steve Wright, "Storming Heaven: Class Composition and Struggle in Italian Autonomist Marxism" (Pluto Press, 2002; pirated at libcom.org)

Movement of 1977

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Movement_of_1977

Judge Calogero

https://www.infoaut.org/storia-di-classe/7-aprile-1979-teorema-calogero

Mike Greco the salami king

https://www.pulselive.co.ke/the-new-york-times/world/mike-greco-salami-king-of-bronxs-little-italy-dies-at-89/b65qyze